The GPU Notes - Part 1

My notes on learning and using GPU and CUDA for Machine Learning, Deep Learning and Software Engineering problems. Most of the content has been inspired from the book “Programming Massively Parallel Processors-4th Edition”.

-

GPU - TFLOPS on Steroids

FLOPS - Floating Point Operations Per Seconds. 1 TFLOPS = 10^12 FLOPS. FLOPS is the number of floating point operations that can be done per second.

Intel i9 processor with 24 CPU cores (latest as of writing this) can reach a peak of 1.3 TFLOPS for single precision i.e. 32-bit floats (or FP32).

Compare this to the H100 GPU which has 16896 CUDA Cores and 640 Tensor Cores (will come later to this) and has limit of 48 TFLOPS for FP32 and 24 TFLOPS for FP64 (double-precision floats also known as ‘double’ in C) for non-tensors and 989 TFLOPS (FP32) and 67 TFLOPS (FP64) for tensors.

Tensor Cores

Latest GPU models also support half precision floats i.e. FP16 with higher TFLOPS (1979 TFLOPS) and FP8 with 3958 TFLOPS. FP8 and FP16 are used in deep learning for mixed precision training (revisited later).

Mixed Precision Training

For understanding floating point representations, refer to one of my earlier posts on floating point compression:

Floating Point Compression -

Smaller but more number of cores

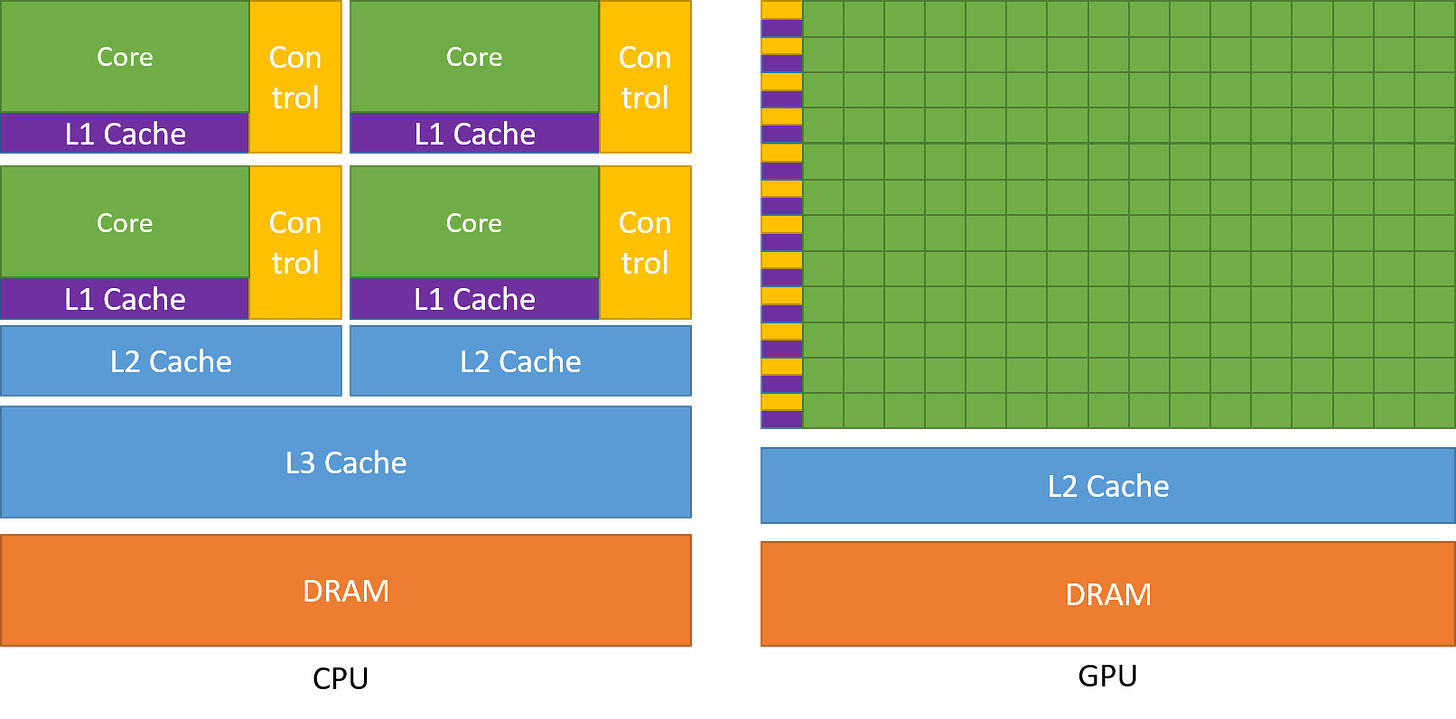

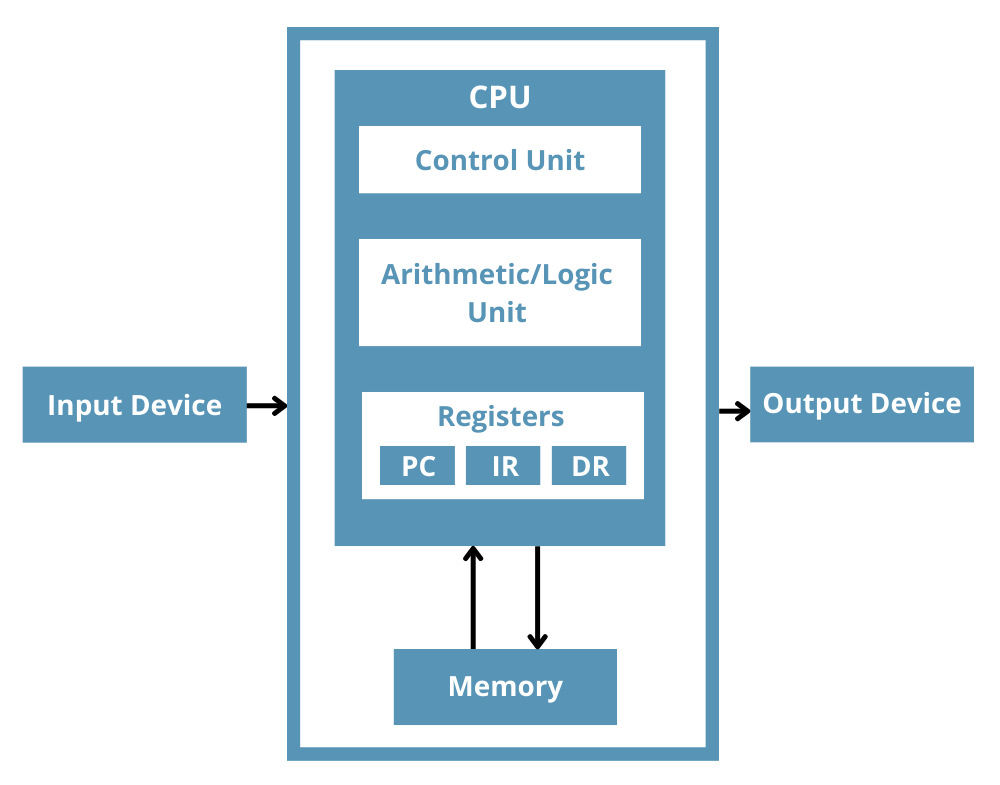

Most commercially available CPUs have 4 to 24 cores and have larger L2 and L3 cache sizes. CPUs also have larger area for control units managing branch prediction etc. Each core also have its own L1 cache (both data and instruction).

Control Unit

CPU Caches

CPUs also have fewer number of channels to the DRAM i.e. the main memory. CPU cores are optimized for low latency whereas GPU cores are optimized for high throughput.

To achieve low latency, CPU needs more number of registers or flip-flops which requires more power and thus one cannot have too many cores inside a CPU. CPUs are good for low latency operations on sequential programs for e.g. computing the first 1 million fibonacci numbers.

Large cache size also allows significant re-use.

Nice write up on CPU architecture

GPUs on the other hand have smaller cores but more number of cores. For example e.g. H100 have 14592 CUDA cores in addition to 640 Tensor cores. They also have smaller caches and smaller control units and more number of channels to the DRAM. The goal is high throughput for parallel computations.

Surface area for the each core in CPU chip is higher as compared to each core in GPU thus enabling more cores in GPU chip.

Smaller cache sizes may force certain applications to be memory bound i.e. most time taken goes into fetching data from DRAM into cache or register. To overcome this drawback more number of smaller caches and more channels enables more number of threads to fetch data in parallel. Thus GPUs have high memory thorughput as compared to CPU. - CUDA Matrix Multiplication

Basic 2D Matrix multiplication using CUDA C++.

#include <stdio.h> #include <iostream> #include <math.h> #include <assert.h> #include <omp.h> #include <cuda.h> #include <cuda_runtime.h> void generate_data(float *x, int n, int m) { static std::random_device dev; static std::mt19937 rng(dev()); std::uniform_real_distribution<float> dist(0.0, 1.0); for (int i = 0; i < n*m; i++) x[i] = dist(rng); } // Matrix multiplication on GPU device __global__ void cuda_mul(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n, int m, int p) { // In CUDA, the ordering of dimensions are reversed i.e. a matrix of dim (N, M, P) will be represented as (P, M, N) in CUDA int row = blockIdx.y*blockDim.y + threadIdx.y; int col = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; if (row < n && col < p) { float res = 0.0; for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) res += a[row*m+i]*b[i*p+col]; c[row*p+col] = res; } } // Matrix multiplication on CPU void mat_mul(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n, int m, int p) { for (int i = 0; i < n*p; i++) c[i] = 0.0; omp_set_num_threads(8); #pragma omp parallel for shared(a, b, c) for(int i = 0; i < n; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < m; j++) { for (int k = 0; k < p; k++) c[i*p+k] += a[i*m+j]*b[j*p+k]; } } } int main(){ int n = 2048; int m = 2048; int p = 2048; float *a, *b, *c, *d; size_t size_a = sizeof(float)*n*m; size_t size_b = sizeof(float)*m*p; size_t size_c = sizeof(float)*n*p; // a, b and c are defined for both CPU and GPU. Thus they can be accessed from both host code and device code cudaMallocManaged(&a, size_a); cudaMallocManaged(&b, size_b); cudaMallocManaged(&c, size_c); generate_data(a, n, m); generate_data(b, m, p); auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now(); // Launch grid and blocks. Each block is 3d and can have maximum of 1024 threads across all dimensions. // Each block has 32 threads in x-direction and 32 in y-direction. // Number of blocks in x direction = #columns in out matrix/#threads in x-direction // In CUDA, the ordering of dimensions are reversed i.e. a matrix of dim (N, M, P) will be represented as (P, M, N) in CUDA dim3 bd(32, 32, 1); dim3 gd(ceil(p/32.0), ceil(n/32.0), 1); // Launch kernel cuda_mul<<<gd, bd>>>(a, b, c, n, m, p); // Synchronize the host and device memory before accessing output cudaDeviceSynchronize(); auto stop = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now(); auto duration = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(stop - start); std::cout << "CUDA Duration = " << duration.count() << " ms" << std::endl; // Compare with multi-threaded matrix multiplication on CPU start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now(); d = (float*)malloc(size_c); mat_mul(a, b, d, n, m, p); stop = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now(); duration = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(stop - start); std::cout << "Standard Duration = " << duration.count() << " ms" << std::endl; cudaFree(a); cudaFree(b); cudaFree(c); free(d); } - Streaming Multiprocessors and Warps

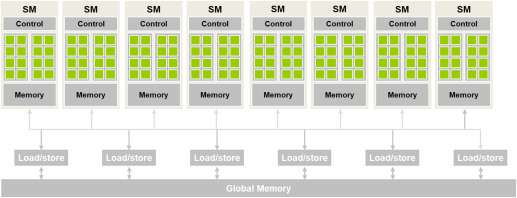

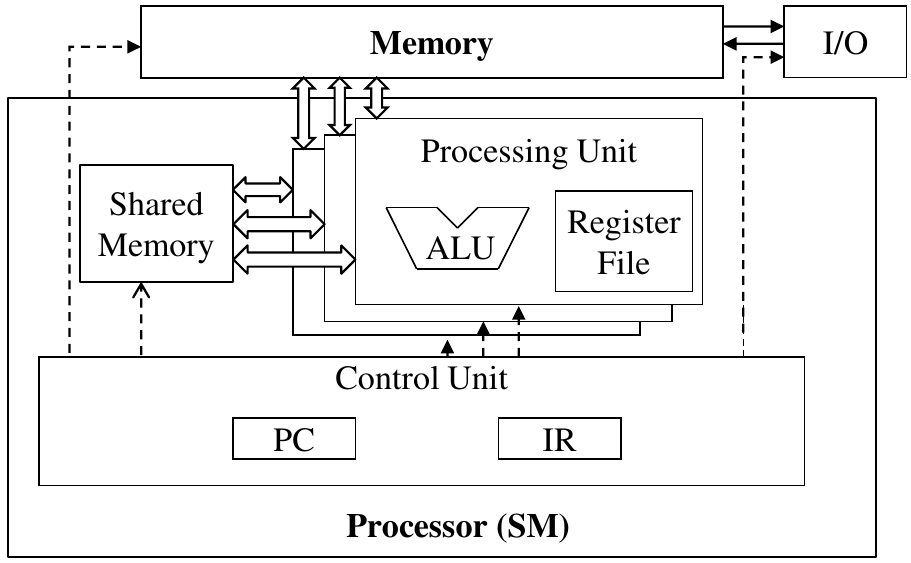

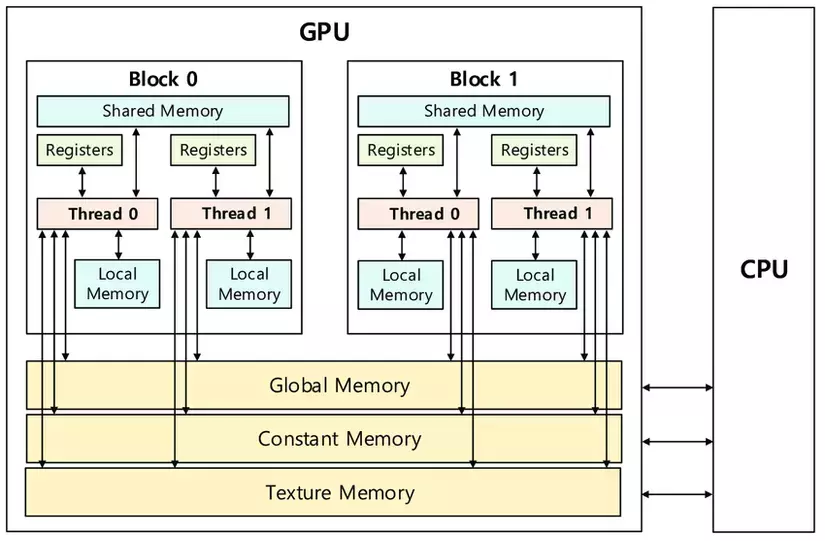

The GPU is arranged as an array of streaming multiprocessors (SM) where each SM contains several streaming processors or CUDA cores, has its own shared memory and control unit. H100 comes with 132 SMs where each SM contains 128 Cores thus totalling 16896 CUDA Cores.

When we launch a grid of threads arranged in a block, the 3d block is linearized in row-major order and distributed across SMs. All threads in a block are assigned to the same SM. Multiple blocks can be assigned to the same SM. All active threads in a SM are run concurrently. H100 supports a maximum of 2048 active threads (that can run concurrently) per SM.

Since all threads in a block run concurrently on the same SM, they would have similar running times. CUDA supports syncing threads using the _syncthreads() method but it is only applicable to threads in same block for the same reason that threads in same block have similar running times.

Thus if the total number of threads in an application is 2^22 and each block has 1024 i.e 2^10 threads, then there are a total of 2^12 blocks of threads. Since each block has 1024 threads and each SM can support 2048 threads, thus each SM can accomodate 2 blocks at a time. Thus, the 1st 2 blocks are assigned to SM0, the next 2 blocks to SM1 and so on. The 132 SMs can accomodate 264 blocks at a time. Thus, the 1st 264 blocks runs concurrently and the remaining blocks are queued. Whenever any one block is completed, one of the queued block is assigned to the SM having capacity.

Note that each SM has only 128 CUDA cores in H100 but can accomodate a maximum of 2048 threads.

The more number of threads assigned per SM is in order to hide latency. If only 128 threads are assigned to a SM, not all threads will be working at all times. Some threads might be busy fetching data from memory and during that time the thread will remain idle. This allows some other thread in the queue to start processing.

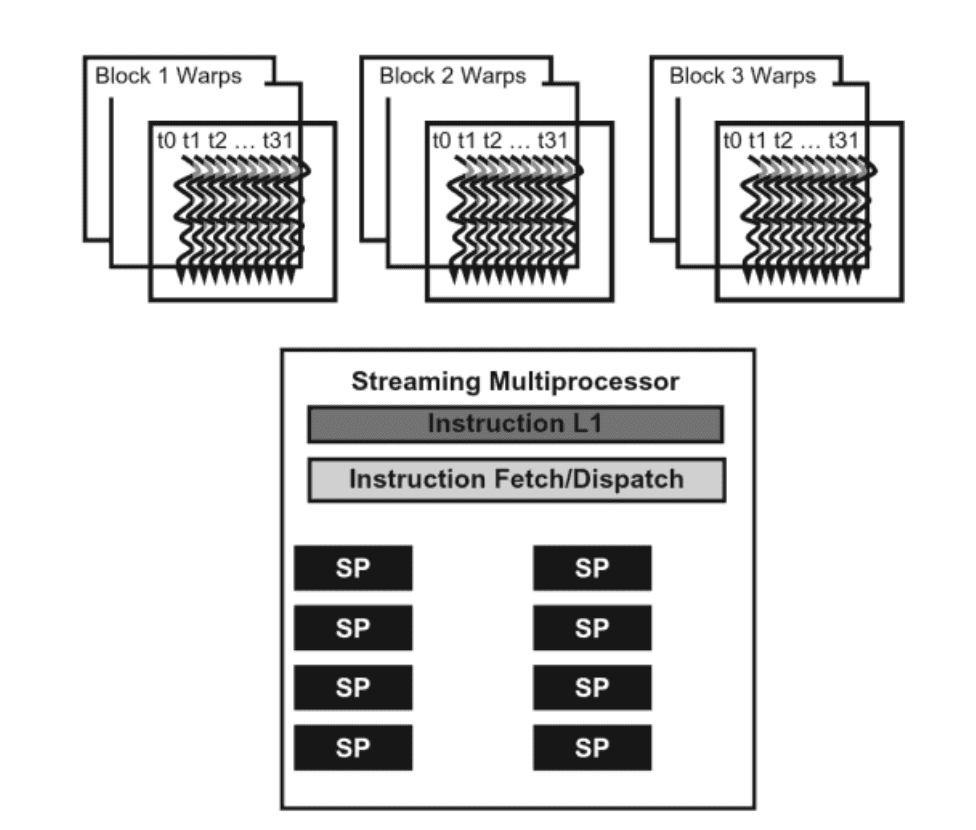

GPUs have smaller control units. Control units fetches instruction into the Instruction Register (IR). The instructions are then parsed. If multiple threads are working on different parts of a program, the amount of instructions to fetch during each instruction cycle will be quite large thus requiring larger control units with larger power requirements.

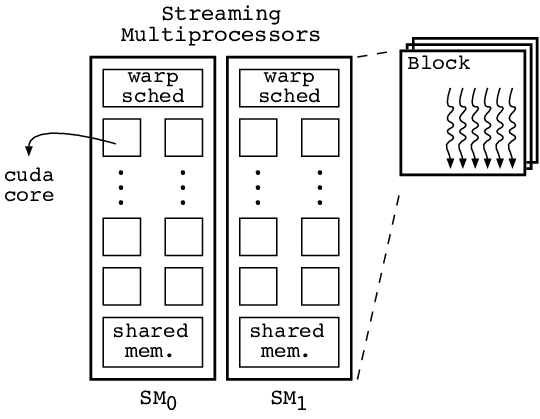

In order to trade-off smaller control units for more number of cores, blocks of threads are partitioned into warps of 32 threads and the 128 cores in SM is partitioned into processing blocks. If each processing block is 16 cores, then there would be 128/16=8 processing blocks in each SM. Threads in the same warp are assigned to the same processing block.

The control unit fetches instruction per warp instead of per thread thus reducing the number of instructions to fetch.

The same instruction is applied to all threads in a SIMD or SIMT (Single Instruction Multiple Thread) fashion. The lane size for SIMD is 32 here.

A single control unit serving for multiple threads.

Since all threads in a warp follow same instruction, a CUDA program having an if-else statement which is dependent on thread index i.e. some threads will execute if statement whereas other threads will execute else statment, will be run twice by all the threads in the warp. First time all the threads will run the if block and next time will run the else block. Threads that should not run the if block will be deactivated during 1st run and similarly threads that should not run the else block will be deactivated during 2nd run.

Control divergence happens here:

__global__ void sq_or_cube(float *a, float *out, int n) { int idx = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; if (idx < n) { if (idx % 2 == 0) out[idx] = a[idx]*a[idx]; else out[idx] = a[idx]*a[idx]*a[idx]; } }

Control divergence happens in 2 places in the above code. First in the check (idx < n) because number of threads could be more than the number of elements. Second here “if (idx % 2 == 0)”.

Role of Warps

CUDA Warp-Level Primitives

Unlike context switching in CPU threads, threads and warps in GPU have low overhead for context switching. As mentioned above, a SM is assigned more threads and warps than the number of available cores because most often warps will sit idle and during that time other warps can run.

Each SM has register file. All threads assigned to a SM have an entry in the register file. When a thread goes out of context the state is saved in the register file which is then load when the thread comes into context again. Thus, threads in SM have zero-overhead scheduling. -

The Occupancy Problem

A SM can accomodate a maximum of 2048 concurrently running threads.

But in practice the number of threads running concurrently in each SM can be lower. For e.g. in H100, the maximum number of blocks that can be assigned concurrently to run on each SM is limited to 32. Thus, if a block has 32 threads, then the number of blocks required for 2048 threads is 64=2048/32. But since only 32 blocks can run concurrently, thus occupancy here is 32*32/2048=50%.

Similarly if a block has 300 threads, then the number of blocks that can be assigned to a SM is int(2048/300)=6. But the number of threads in 6 block is only 1800. Thus the occupancy is 1800/2048=88%.

In H100, a maximum of 65536 registers can be allocated per SM and a maximum of 255 registers per thread. Registers are kind of D-flip flops that are used to store the state of a variable. Thus, any automatic variable declared inside a kernel may be stored in a register. For e.g.float aorint b.

What are registers

Registers in CPU

If some kernel has 200 variables declared, then the number of threads that can be run is only int(65536/200)=327. Thus, the occupancy in this case is 327/2048=16%. -

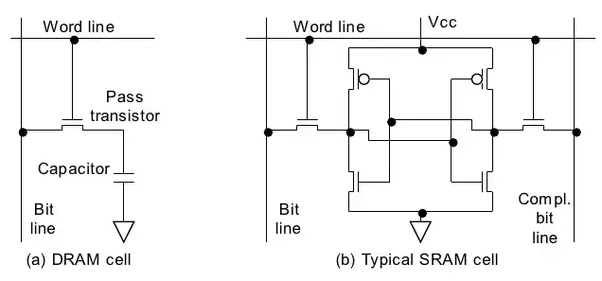

Memory

DRAM is bad for GPU because when you have 1000s of threads accessing the memory simulataneously, it can lead to congestion and unwanted delays. The performance of a GPU kernel is measured in TFLOPS i.e. number of (Tera) floating point operations per second.

DRAM vs SRAM

If you take the matrix multiplication kernel above, the innermost loop fetches two floating point numbersa[row*m+i]andb[i*p+col]each 4 bytes (32-bit floats) from the DRAM and does 1 multiplication and 1 addition. Thus the FLOP/B ratio is 2/8 =0.25 FLOP/B. The memory bandwidth of H100 is around 2TB/s. Thus, TFLOPS can be calculated by taking the product of bandwidth and FLOP/B i.e. 2*0.25=0.5 TFLOPS.

The peak TFLOPS achievable with H100 is around 48 TFLOPS for 32-bit floats. Thus, efficiency of the matrix multiplication kernel above is only 0.5/48=1.0%.

To achieve 48 TFLOPS, the kernel needs to perform 24 FLOP/B or 192 floating point operations for each byte of data read from the DRAM.

This can only be achieved if we re-use the data read from DRAM.

Similar to CPU and RAM, where the different memory types in order of increasing access latencies and increasing memory sizes:

register < L1 cache < L2 cache < L3 cache < Main Memory (RAM)

GPUs also have hierarchy of memory access latencies. Similar to the RAM, the highest access latency and highest memory size is the GPU global memory (DRAM). In H100, the global memory size is 188GB HBM3 with a bandwidth of 2TB/s. The scope of the global memory is the kernel grid i.e. all threads in a grid see the same memory. This is off-chip memory.

Registers are implemented per SM and scoped per thread i.e. each thread has its own set of registers has the lowest latency and is implemented on-chip. For e.g. variables declared likeint aorfloat bare usually stored in registers. H100 accomodates a maximum of 65536 registers per SM and 255 maximum per thread.

Stack vs Heap Memory

For pointers and arrays such asfloat *aorint[] aare stored in something known as local memory which is same as global memory but is scoped per thread.

Shared Memory is an important type of memory that is also implemented on-chip and has very low access latency. It is scoped per block of thread i.e. all threads in a block see the same shared memory addresses. The size of shared memory is configurable and maximum is 228KB in H100. To re-use data from global memory such as pointers and arrays, they are often stored in the shared memory which improves TFLOPS.

Similar to CPU, GPUs have L1 cache scoped per SM and L2 cache scoped across all SM. Each SM has its own L1 cache. The combined size of L1 cache + Shared memory is 256KB in H100.

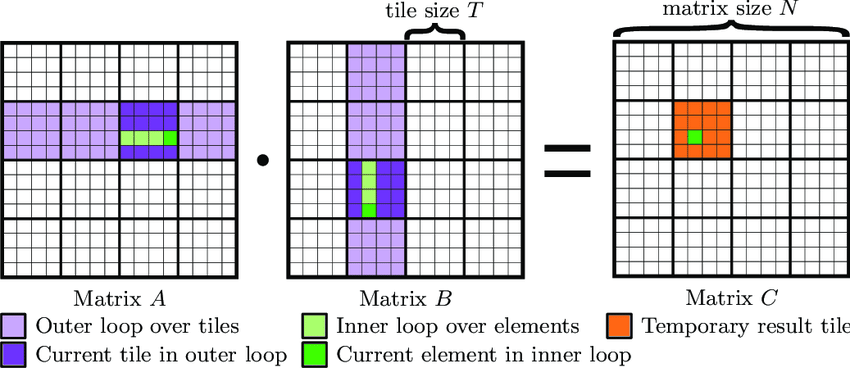

L2 cache size is around 50MB and is common to all SMs. - Tiled Matrix Multiplication

Matrix multiplication kernel (see above) using tiling to use shared memory and cache values to improve throughput.

In the matrix multiplication kernel above, each row of matrix a is multiplied with p columns of matrix b and similarly each column of b is multiplied with n rows of a. Thus, we can cache the matrices a and b in the shared memory and re-use the cached matrix values for the matrix product instead of fetching from DRAM.

// TILE_WIDTH is same as block dimension in each x and y direction #define TILE_WIDTH 32 // Divide the matrices a and b into square tiles of dim TILE_WIDTH*TILE_WIDTH. // Each tile here corresponds to one block of threads. __global__ void cuda_mul_tiled(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n, int m, int p) { // Current thread index in output block is (threadIdx.y, threadIdx.x). // Current output element index is (blockIdx.y*blockDim.y + threadIdx.y, blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x) // For this case: blockDim.y = TILE_WIDTH and blockDim.x = TILE_WIDTH // Each block of threads will have its own copy of Mds and Nds arrays in the shared memory. // Thus indexing of Mds and Nds arrays happens at the block level. __shared__ float Mds[TILE_WIDTH*TILE_WIDTH]; __shared__ float Nds[TILE_WIDTH*TILE_WIDTH]; int bx = blockIdx.x; int by = blockIdx.y; int tx = threadIdx.x; int ty = threadIdx.y; int row = by*TILE_WIDTH + ty; int col = bx*TILE_WIDTH + tx; float res = 0.0; // Number of "column-tiles" in a is m/TILE_WIDTH where m is number of columns in a. // Number of "row-tiles" in b is m/TILE_WIDTH where m is number of rows in b. // Instead of looping over 0 to m-1, first loop over each tile and then loop over each element of the tile. for (int ph = 0; ph < ceil(m/float(TILE_WIDTH)); ph++) { // The current index in the output block is (ty, tx) and width of block is TILE_WIDTH // The current row index of a is 'row=blockIdx.y*TILE_WIDTH + threadIdx.y'. // Note that TILE_WIDTH=blockDim.y are same in this case. // The current column index of a is 'col=ph*TILE_WIDTH + tx'. ph is the index of column-tile. if (row < n && (ph*TILE_WIDTH + tx) < m) Mds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+tx] = a[row*m + ph*TILE_WIDTH + tx]; else Mds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+tx] = 0.0f; // The current row index of b is 'row=ph*TILE_WIDTH+ty'. // Note that TILE_WIDTH=blockDim.x are same in this case. // The current column index of b is 'col=blockIdx.x*TILE_WIDTH + threadIdx.x'. if ((ph*TILE_WIDTH + ty) < m && col < p) Nds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+tx] = b[(ph*TILE_WIDTH+ty)*p + col]; else Nds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+tx] = 0.0f; // __syncthreads syncs all threads in the same block only. // Thus all threads in the same block first finishes computing the Mds and Nds arrays for current output tile corresponding to output 'row' and 'col' and then computes the sum of products. __syncthreads(); for (int i = 0; i < TILE_WIDTH; i++) res += Mds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+i]*Nds[i*TILE_WIDTH+tx]; // The partial sum for the current tile block is calculated before all the threads calculates the partial sum for next tile block. __syncthreads(); } if (row < n && col < p) c[row*p+col] = res; }

In the next part of the post we will look at CUDA optimizations thorugh different examples of data structures and algorithms.