The GPU Notes - Part 2

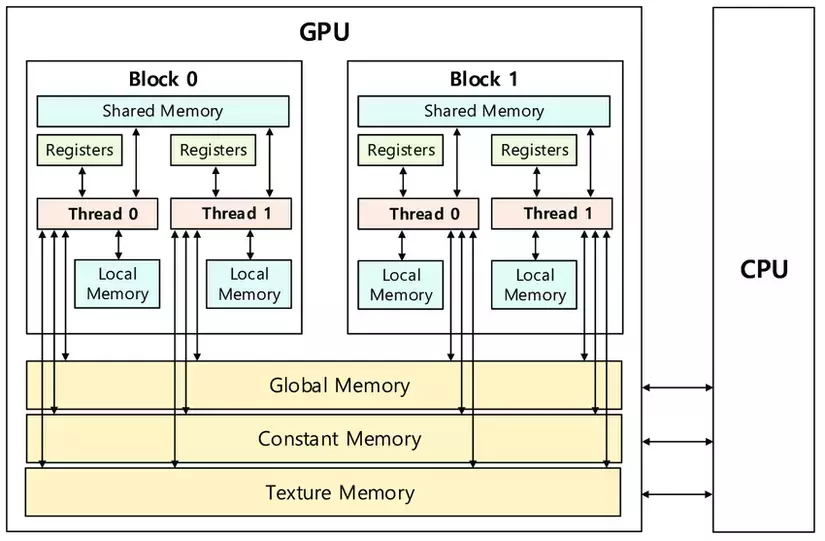

In the previous post, I started jotting down my learnings with GPU and CUDA programming and explored some of the fundamentals of GPU architecture and memory. Towards the end, we saw how we can speed up memory access in matrix multiplication in order to increase TFLOPS by using shared memory tiling. In this part we will look at some GPU optimization techniques through examples.

- Memory Coalescing

In the previous post we saw that reading from global memory in GPU is slow because firstly they are implemented off-chip and secondly they are implemented using the DRAM cells. Shared memory and caches on the other hand are implemented on-chip and using SRAM cells. SRAM is much faster as compared to DRAM.

DRAM vs SRAM

Similar to cache lines in CPU, when a location in the global memory is accessed, “nearby” locations are also accessible in the same CPU cycle. This saves number of CPU cycles to read the data from global memory. In CPU, the cache line size is usually 64-bytes. Once read from RAM they are stored in either L1, L2 or L3 cache.

Demystifying CPU Caches with Examples

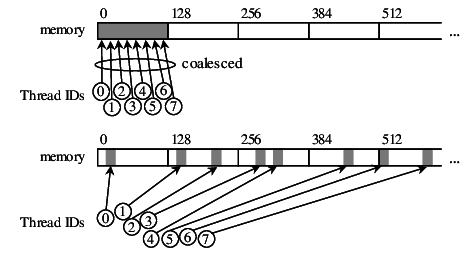

Threads in a warp (group of 32 threads) follow the same instruction (SIMD model) and as a result the threads in warp access consecutive memory locations in the global memory. Global memory addresses are 128-byte aligned and thus accessing 4-byte floats (fp32) by a warp of 32 threads can be done in a single pass (coalesced). Each 128-byte segment in global memory is termed as a burst.

Memory Coalescing Techniques

Memory Access Coalescing

Accessing with offset or strided access patterns are not coalesced as shown in the below examples.

__global__ void offset_add(float *inp, float *oup, int n, int offset) { // When offset=0, access is coalesced but if offset=1, then some threads in a warp will read data from burst i // and the remaining from burst i+1. // In the worst case, each thread reads two bursts from the global memory. int index = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; index += offset; oup[index] = inp[index] + 100.0; } __global__ void strided_add(float *inp, float *oup, int n, int stride) { // When stride=1, access is coalesced but if stride=2, // then some threads in a warp will read data from burst i and the remaining from burst 2i. // In the worst case, each thread reads 32 bursts from the global memory // because when stride >= 32 each thread in a warp reads from a different burst. int index = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; index *= stride; oup[index] = inp[index] + 100.0; }

Performance takes a major hit when using strided global memory access. The strided access pattern takes almost 10x (on RTX4050) the time it takes for coalesced or offset access for the same number of input elements and same number of threads.

GPU Performance

In the matrix multiplication kernel we saw in the previous part:__global__ void cuda_mul(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n, int m, int p) { int row = blockIdx.y*blockDim.y + threadIdx.y; int col = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; if (row < n && col < p) { float res = 0.0; for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) res += a[row*m+i]*b[i*p+col]; c[row*p+col] = res; } }

Each thread in a warp is responsible for calculating each element of matrix c laid out in row-major order, thus threads at indices (x, y) and (x, y+1) calculatesc[x][y]andc[x][y+1]respectively. Thus, access to matrix c is coalesced.

Consecutive threads at indices (x, y) and (x, y+1) reads the same elements from row x of matrix a and thus uses the same burst from the global memory except at the edges for e.g. (x, y+m-1) and (x+1, 0) which reads 2 different rows x and x+1 from a with a stride of m (column width) and are not coalesced.

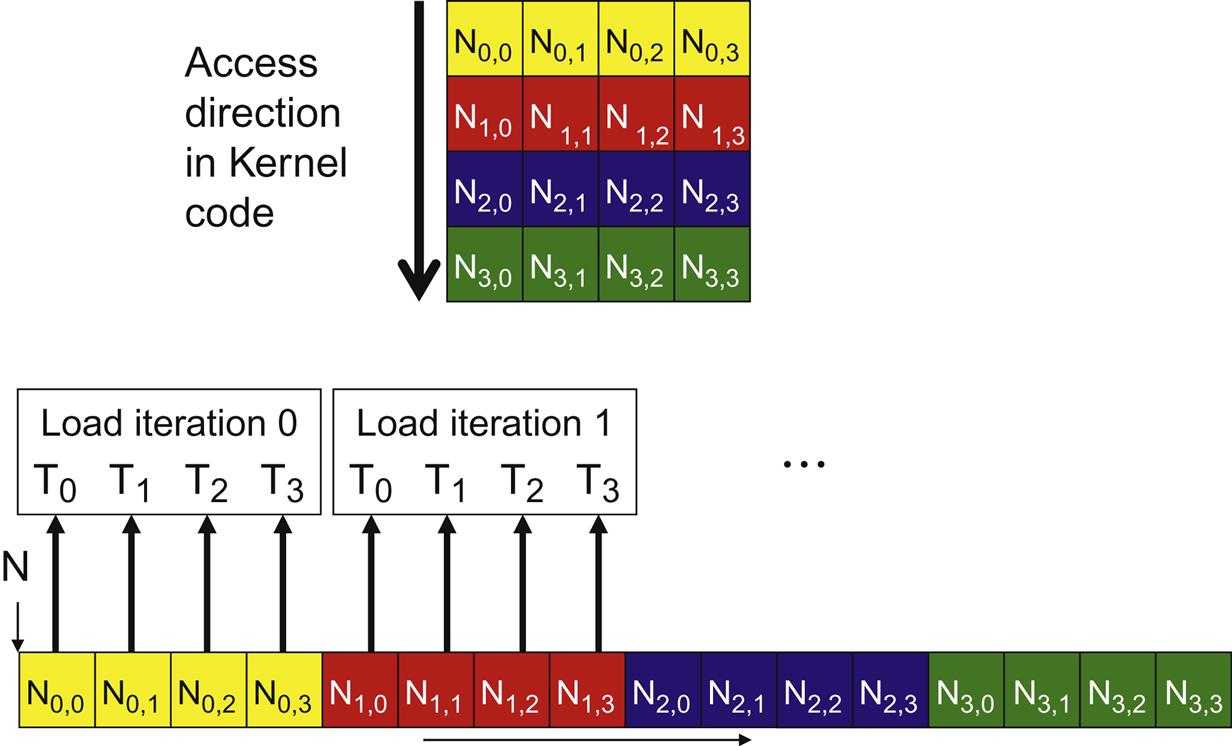

For matrix b, the threads at indices (x, y) and (x, y+1) reads consecutive columns y and y+1 and thus are coalesced.

In the above matrix, elements are laid out in row-major order and threads are also aligned in row-major order. Consecutive threads are accessing consecutive columns from the matrix in the global memory and thus access is coalesced. This is the case for matrix b in our matrix multiplication code.

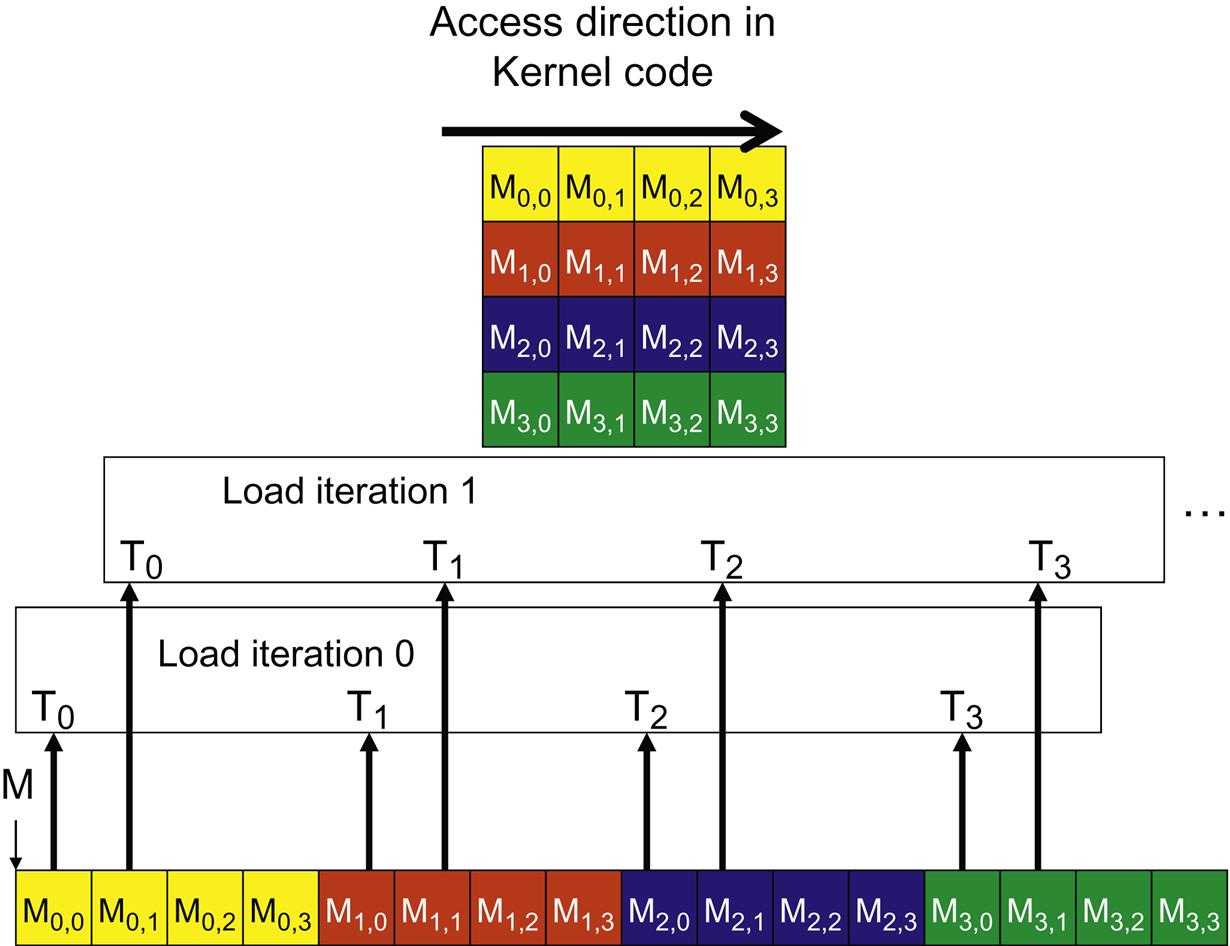

But if instead of the multiplicationc=a.b, it was transpose of b i.e.c=a.bT, then consecutive thread access to elements of b are not coalesced and are strided by size of m and thus would perform worse thanc=a.b.

In the above kernel instead of passing the transpose of b, we are interchanging the x and y coordinates of b during access.__global__ void cuda_mul_bt(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n, int m, int p) { int row = blockIdx.y*blockDim.y + threadIdx.y; int col = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; if (row < n && col < p) { float res = 0.0; for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) res += a[row*m+i]*b[col*m+i]; c[row*p+col] = res; } }

In the above matrix, although the elements are laid out in row-major order but since we need to access the transpose of the matrix, thus the threads needs to access in column-major order. Consecutive threads are accessing consecutive rows which are stride by column-size width and thus access is not coalesced.

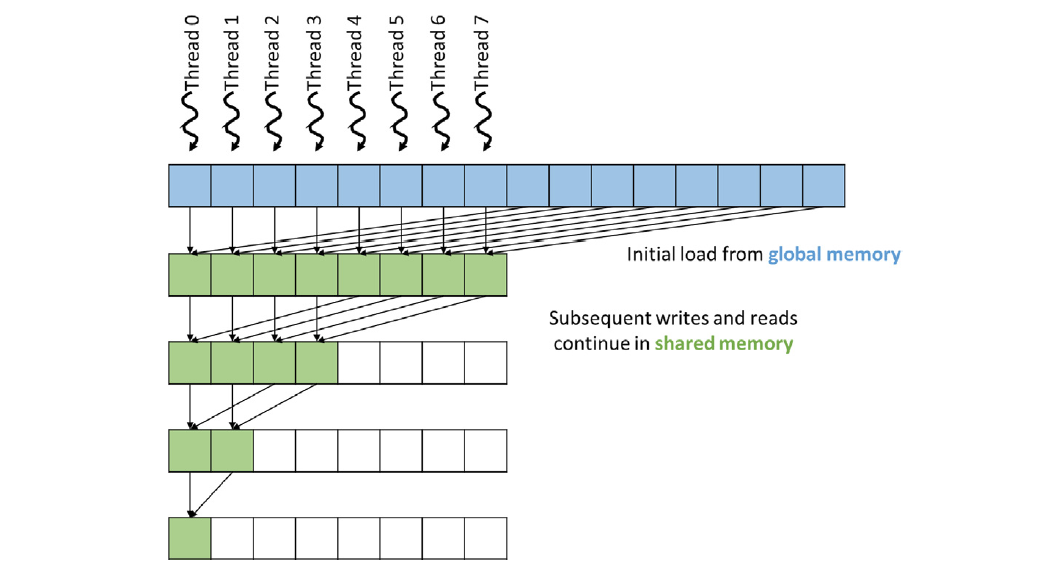

One possible solution to overcome the problem with non-coalesced access in matrix transpose multiplication is to use the shared memory with tiling as we saw in the previous part. With shared memory tiling, the matrix b is loaded in transpose from global memory to shared memory first, the multiplication between the elements of a and b happens with data from shared memory.

Using Shared Memory in CUDA C/C++

But as noted in the above post, shared memory is divided into banks. Shared memory is divided into 32 banks where each bank is responsible for 32 consecutive bits. But if more than one thread in a warp accesses the same bank, then a bank conflict happens and request is serialized for those threads in the warp. Bank conflict is bound to happen with F64 data type i.e. double precision floats of 64-bits because even if each thread access 2 consecutive banks, only 16 threads will have parallelized access out of 32 threads in a warp.

In latest drivers, one can configure bank size for e.g. usingcudaDeviceSetSharedMemConfig()we can set the bank size to either 4 bytes i.e. 32 bits or 8 bytes i.e 64 bits.

A matrix multiplication kernel using transpose of b and shared memory tiling to improve performance.__global__ void cuda_mul_bt_tiled(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n, int m, int p) { __shared__ float Mds[TILE_WIDTH*TILE_WIDTH]; __shared__ float Nds[TILE_WIDTH*TILE_WIDTH]; int bx = blockIdx.x; int by = blockIdx.y; int tx = threadIdx.x; int ty = threadIdx.y; int row = by*TILE_WIDTH + ty; int col = bx*TILE_WIDTH + tx; float res = 0.0; for (int ph = 0; ph < ceil(m/float(TILE_WIDTH)); ph++) { if (row < n && (ph*TILE_WIDTH + tx) < m) Mds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+tx] = a[row*m + ph*TILE_WIDTH + tx]; else Mds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+tx] = 0.0f; // load the elements of b into shared memory by accessing consecutive rows instead of columns // this is uncoalesced access if ((ph*TILE_WIDTH + ty) < m && col < p) Nds[tx*TILE_WIDTH+ty] = b[col*m + (ph*TILE_WIDTH+ty)]; else Nds[tx*TILE_WIDTH+ty] = 0.0f; __syncthreads(); for (int i = 0; i < TILE_WIDTH; i++) res += Mds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+i]*Nds[tx*TILE_WIDTH+i]; __syncthreads(); } if (row < n && col < p) c[row*p+col] = res; }

With matrix sizes of 2048x2048, it takes somewhere around 1100ms for multiplication with transpose without shared memory tiling and around 750ms with shared memory tiling on my RTX4050 running on WSL Ubuntu. Some good reads on shared memory and efficient matrix transpose or multiplication kernels.

An Efficient Matrix Transpose in CUDA C/C++

Optimizing Matrix Transpose in CUDA

Access Global Memory Efficiently in CUDA C/C++ Kernels - Thread Coarsening

In all of the CUDA examples we saw, each thread has been assigned the task for computing one output element. For e.g. in vector addition or matrix multiplication, each thread in a block is assigned the task of computing one output element. This is useful if there are enough resources such as number of threads per block, shared memory etc. But in many practical problems, having too many threads can lead to redundant loading of data, synchronization overhead, redundant work.

To overcome such issues, one possible optimization is to reuse a thread to perform multiple computations. Without proper benchmarking this can lead to unused GPU resources.

A matrix multiplication (with b transpose) kernel with thread coarsening where each thread is responsible for calculating 4 elements of the output matrix.

// COARSE_FACTOR is the number of outputs computed by a single thread #define COARSE_FACTOR 4 __global__ void cuda_mul_coarsened(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n, int m, int p) { __shared__ float Mds[TILE_WIDTH*TILE_WIDTH]; __shared__ float Nds[TILE_WIDTH*TILE_WIDTH]; int bx = blockIdx.x; int by = blockIdx.y; int tx = threadIdx.x; int ty = threadIdx.y; int row = by*TILE_WIDTH + ty; // Each row is multiplied and summed with 4 consecutive columns to get 4 consecutive values. int col_start = bx*TILE_WIDTH*COARSE_FACTOR + tx; // Instead of storing in a variable, the outputs are stored in an array. Most likely it will use local memory instead of a register. float Pval[COARSE_FACTOR]; for (int r = 0; r < COARSE_FACTOR; r++) Pval[r] = 0.0f; for (int ph = 0; ph < ceil(m/float(TILE_WIDTH)); ph++) { if (row < n && (ph*TILE_WIDTH + tx) < m) Mds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+tx] = a[row*m + ph*TILE_WIDTH + tx]; else Mds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+tx] = 0.0f; // For each of the 4 columns of matrix b load upto 4 different tiles into shared memory. for (int r = 0; r < COARSE_FACTOR; r++) { int col = col_start + r*TILE_WIDTH; if ((ph*TILE_WIDTH + ty) < m && col < p) Nds[tx*TILE_WIDTH+ty] = b[col*m + (ph*TILE_WIDTH+ty)]; else Nds[tx*TILE_WIDTH+ty] = 0.0f; __syncthreads(); for (int i = 0; i < TILE_WIDTH; i++) Pval[r] += Mds[ty*TILE_WIDTH+i]*Nds[tx*TILE_WIDTH+i]; __syncthreads(); } } for (int r = 0; r < COARSE_FACTOR; r++) { int col = col_start + r*TILE_WIDTH; if (row < n && col < p) c[row*p+col] = Pval[r]; } }

For the matrix multiplication kernel with transpose in the above section, with a COARSE_FACTOR of 4, it takes somewhere around 550ms as compared to 750ms without coarsening.

Thread coarsening and register tiling

To find the optimum value of the COARSE_FACTOR, we can experiment with different values and check the stats. - Convolution Kernel

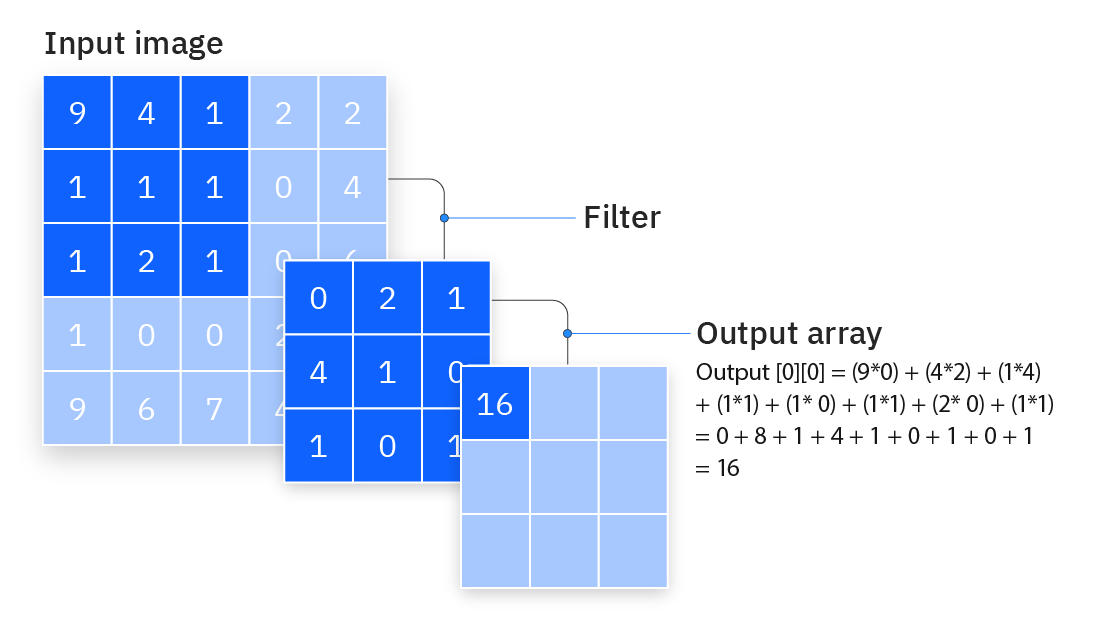

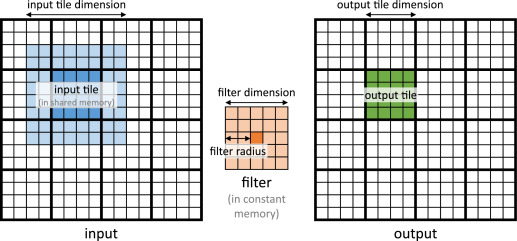

Convolution is one of the most common operation used in deep learning. 2D and 3D convolutions are used for image and video based ML problems whereas 1D convolutions are primarily used for text based ML problems. They operate like a sliding window to capture neighborhood information. Below image depicts how convolution works.

2D Convolution in Image Processing

PyTorch 2D Convolution

Example of 2D Convolution

A very basic implementation of a 2D convolution with a filter size of K where K is assumed to be odd integer usually small in the range of[3, 15]. The input matrix isaand the filter matrix isFand filter size isK.

__global__ void conv2D_basic(float *a, float *F, float *out, int K, int n, int m) { int row = blockIdx.y*blockDim.y + threadIdx.y; int col = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; float res = 0.0f; for (int i = 0; i < K; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < K; j++) { int u = row-(K-1)/2+i; int v = col-(K-1)/2+j; // check the boundaries if (u >= 0 && u < n && v >= 0 && v < m) res += a[u*m+v]*F[i*K+j]; } } if (row < n && col < m) out[row*m+col] = res; }

Similar to the matrix multiplication kernel, the above convolution has OP/B ratio of only 0.25 i.e. for every 8 byte of data loaded from DRAM, only 2 operations (1 multiplication and 1 addition) are performed. This can be improved by using shared memory, constant memory and/or caches. Another major problem arising in the convolution operation is control divergence occurring due to the if else checks happening at the boundaries of the input matrix. Threads in a warp are supposed to follow SIMD but with if-else condition, SIMD breaks. Threads in warps near the boundaries will have different paths and hence divergence happens.

Warp Control Divergence

For small input matrices as compared to the filter matrix, the proportion of threads involved in control divergence is significant whereas for very large input matrix as compared to the filter matrix, control divergence becomes insignificant.

To improve OP/B performance, 1st step is to put the filter matrix in constant memory. Constant memory is implemented using DRAM and is off-chip but it is read-only. When the data is loaded from constant memory, it hints the GPU that the data should be cached on-chip in either L1 or L2 cache as aggressively as possible. Thus, the data is loaded from constant memory only once, for future invocations, it is served from either L1 or L2 cache. Below is an implementation using constant memory for the filter matrix.// filter size #define K 11 // constant memory is declared outside any function __constant__ float F_c[K*K]; __global__ void conv2D_constant_mem(float *a, float *out, int n, int m) { int row = blockIdx.y*blockDim.y + threadIdx.y; int col = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; float res = 0.0f; for (int i = 0; i < K; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < K; j++) { int u = row-(K-1)/2+i; int v = col-(K-1)/2+j; if (u >= 0 && u < n && v >= 0 && v < m) res += a[u*m+v]*F_c[i*K+j]; } } if (row < n && col < m) out[row*m+col] = res; } int main() { int n = 1e4; int m = 1e3; float *a, *f, *out; cudaMallocManaged(&a, n * m * sizeof(float)); cudaMallocManaged(&f, K * K * sizeof(float)); cudaMallocManaged(&out, n * m * sizeof(float)); // copies f directly to constant memory cudaMemcpyToSymbol(F_c, f, K * K * sizeof(float)); dim3 bd(32, 32, 1); dim3 gd(ceil(m/32.0), ceil(n/32.0), 1); conv2D_constant_mem<<gd, bd>>(a, out, n, m); cudaDeviceSynchronize(); cudaFree(a); cudaFree(f); cudaFree(out); }

Using constant memory, the OP/B ratio is doubled because now 4 bytes (only input matrix elements) is loaded from DRAM for 2 operations i.e. OP/B ratio is 0.5. The filter matrix elements are served from cache. Similar to matrix multiplication, the input matrix can be loaded into shared memory and we can perform the convolution using tiling.#define K 11 // Thread block size is equal to the OUT_TILE_WIDTH #define OUT_TILE_WIDTH 32 // INP_TILE_WIDTH includes additional (K-1)/2 rows and columns on either side of output tile #define INP_TILE_WIDTH (OUT_TILE_WIDTH + (K-1)) // constant memory is declared outside any function __constant__ float F_c[K*K]; __global__ void conv2D_shared_mem(float *a, float *c, int n, int m) { // shared memory size is INP_TILE_WIDTH*INP_TILE_WIDTH // but block size is OUT_TILE_WIDTH*OUT_TILE_WIDTH __shared__ float a_s[INP_TILE_WIDTH*INP_TILE_WIDTH]; int row = blockIdx.y*OUT_TILE_WIDTH + threadIdx.y; int col = blockIdx.x*OUT_TILE_WIDTH + threadIdx.x; // Since the number of elements in input tile is greater than the number of threads in a block // each thread thus loads multiple input tile elements from DRAM into shared memory. int index = threadIdx.y*OUT_TILE_WIDTH + threadIdx.x; for (int i = index; i < INP_TILE_WIDTH*INP_TILE_WIDTH; i += OUT_TILE_WIDTH*OUT_TILE_WIDTH) { // get the index in shared memory array int u = i/INP_TILE_WIDTH; int v = i % INP_TILE_WIDTH; // get the absolute index int p = blockIdx.y*OUT_TILE_WIDTH - (K-1)/2 + u; int q = blockIdx.x*OUT_TILE_WIDTH - (K-1)/2 + v; if (p >= 0 && p < n && q >= 0 && q < m) a_s[i] = a[p*m+q]; else a_s[i] = 0.0f; } __syncthreads(); // run convolution with shared memory once the input tile is loaded. float res = 0.0f; for (int i = 0; i < K; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < K; j++) { int u = threadIdx.y+i; int v = threadIdx.x+j; res += a_s[u*INP_TILE_WIDTH+v]*F_c[i*K+j]; } } if (row < n && col < m) c[row*m+col] = res; } int main(){ int n = 1e4; int m = 1e3; float *a, *f, *out; cudaMallocManaged(&a, n*m*sizeof(float)); cudaMallocManaged(&f, K*K*sizeof(float)); cudaMallocManaged(&out, n*m*sizeof(float)); cudaMemcpyToSymbol(F_c, f, K*K*sizeof(float)); dim3 bd(OUT_TILE_WIDTH, OUT_TILE_WIDTH, 1); dim3 gd(ceil(m/float(OUT_TILE_WIDTH)), ceil(n/float(OUT_TILE_WIDTH)), 1); conv2D_shared_mem<<<gd, bd>>>(a, out, n, m); cudaDeviceSynchronize(); cudaFree(a); cudaFree(f); cudaFree(out); }

Standard CPU convolution on a matrix of size 1e4 x 1e3 and filter size of 11x11 takes somewhere around 700ms whereas both the GPU kernel based convolutions (with and without shared memory tiling) takes somewhere around only 20ms.

We can approximately calculate the OP/B ratio for the above kernel as follows: For each input tile loaded into shared memory, total number of (approx) bytes read from the DRAM isINP_TILE_WIDTH*INP_TILE_WIDTH*4. For each element of the input tile, multiply the filter matrix of dimK*KwithK*Kelements of the input tile resulting inK^2multiplications and then there areK^2additions to sum up the products. This is repeated for all elements of the input tile i.e. number of operations =INP_TILE_WIDTH^2 * K^2 * 2. The OP/B ratio is:(INP_TILE_WIDTH^2 * K^2 * 2)/(INP_TILE_WIDTH^2 * 4) = K^2/2.

Larger filter sizes has greater OP/B ratio because each input element is used by more threads.

The actual calculation is a bit complex since at the boundaries the input tile has fewer thanINP_TILE_WIDTH*INP_TILE_WIDTHelements and also some input tile elements are loaded by multiple blocks of threads as they are overlapping.

The elements in the input tile that are located at the boundaries of the output tile are called the halo cells as they are not part of the output but is required to calculate the output values by multiplying with the filter.

One issue with the above kernel is that for elements at the boundaries, we have to unnecessarly iterate over “non-existent” indices to load the input tile into shared memory. This consumes GPU cycles. Also, for multiple output tiles, there is overlap between the input tile elements and thus the same input tile element might be loaded by multiple blocks into the shared memory and thus duplicating effort. Duplicate loading cannot be avoided as shared memory is scoped per block. One possible solution to this is not to load the halo cells and fetch them directly from DRAM and hope that DRAM caches the halo cell values.__global__ void conv2D_shared_mem(float *a, float *c, int n, int m) { __shared__ float a_s[OUT_TILE_WIDTH*OUT_TILE_WIDTH]; int row = blockIdx.y*OUT_TILE_WIDTH + threadIdx.y; int col = blockIdx.x*OUT_TILE_WIDTH + threadIdx.x; // Load the input tile (without halo cells) into shared memory if (row < n && col < m) a_s[threadIdx.y*OUT_TILE_WIDTH + threadIdx.x] = a[row*m + col]; else a_s[threadIdx.y*OUT_TILE_WIDTH + threadIdx.x] = 0.0f; __syncthreads(); float res = 0.0f; for (int i = 0; i < K; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < K; j++) { // local block indices int u = threadIdx.y-(K-1)/2+i; int v = threadIdx.x-(K-1)/2+j; // global indices int w = row-(K-1)/2+i; int z = col-(K-1)/2+j; // if local indices are of halo cells then read directly from global memory else use shared memory if (u >= 0 && u < OUT_TILE_WIDTH && v >= 0 && v < OUT_TILE_WIDTH) res += a_s[u*OUT_TILE_WIDTH+v]*F_c[i*K+j]; else if (w >= 0 && w < n && z >= 0 && z < m) res += a[w*m+z]*F_c[i*K+j]; } } if (row < n && col < m) c[row*m+col] = res; } - Reduction and atomic operations

So far all the problems we have solved using CUDA are conflict free i.e. each output computed by a thread is independent of any other output computed by another thread. As you know that when working with threads in CPU, most practical problem requires thread-safety. For e.g. in the classic example ofx = x+1, if x=10 and 2 threads A and B is incrementing x simulataneously, then there is a chance of race-condition. Threads A reads x=10, increments x by 1 to 11 but before updating x in the register or memory thread B reads x but since x has not yet updated, B will also read x=10. As a result bit A and B updates x to 11.

In GPU, similar race conditions can happen using threads.

Let’s look at the 1st problem of parallel histogram calculation where given a stream of characters in a-z, we need to calculate the frequencies of bucket of size b. For e.g. if b=4, then the buckets are[a-d],[e-h],[i-l],[m-p],[q-t],[u-x], and[y-z]. Thus whenever we encounter some character, we find the bucket where it should lie and then increment the count of that bucket. For e.g. if character isg, then it should lie in the bucket[e-h].

A simple CPU version of the problem:void histogram(char *s, int *histo, int n, int m, int b) { // buckets are stored in histo array where it is assumed that each // bucket corresponds to an index. For e.g. [a-d] is index 0, [e-h] // is index 1 and so on. Thus getting bucket index for character is // done by dividing the index of character by bucket size i.e. 4. for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) { char c = s[i]; int c_int = c - 'a'; histo[c_int/b] += 1; } } int main() { int n = 1e5; int b = 4; int m = ceil(26.0/b); char *s = (char *)malloc(n*sizeof(char)); // generate some random stream of characters of size n here. int *histo = (int *)malloc(m*sizeof(int)); for (int i = 0; i < m ; i++) histo[i] = 0; histogram(s, histo, n, m, b); free(s); free(histo); }

In order to parallelize the above, we can have each thread operate on each character in the input.__global__ void cuda_histogram(char *s, int *histo, int n, int m, int b) { // buckets are stored in histo array where it is assumed that each // bucket corresponds to an index. For e.g. [a-d] is index 0, [e-h] // is index 1 and so on. Thus getting bucket index for character is // done by dividing the index of character by bucket size i.e. 4. int index = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; if (index < n) { char c = s[index]; int c_int = c - 'a'; histo[c_int/b] += 1; } } int main() { int n = 1e5; int b = 4; int m = ceil(26.0/b); char *s; int *histo; cudaMallocManaged(&s, n*sizeof(char)); cudaMallocManaged(&histo, m*sizeof(int)); // generate some random stream of characters of size n here. for (int i = 0; i < m ; i++) histo[i] = 0; cuda_histogram<<<ceil(n/1024.0), 1024>>>(s, histo, n, m, b); cudaFree(s); cudaFree(histo); }

But note that when multiple threads are updatinghisto[c_int/b]it can lead to race condition. CUDA provides functions for atomic operations such as atomicAdd() for addition, atomicMul() for multiplication and so on.

Atomic functions in cuda__global__ void cuda_histogram(char *s, int *histo, int n, int m, int b) { // buckets are stored in histo array where it is assumed that each // bucket corresponds to an index. For e.g. [a-d] is index 0, [e-h] // is index 1 and so on. Thus getting bucket index for character is // done by dividing the index of character by bucket size i.e. 4. int index = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; if (index < n) { char c = s[index]; int c_int = c - 'a'; atomicAdd(&(histo[c_int/b]), 1); } }

Atomic operations have penalty on performance. When multiple threads are operating on atomic functions, they are effectively serialized. Thus, performance degrades in the case of parallel histogram if many threads are writing to the same bucket index. All threads reading and writing to same bucket index will be serialized.

We can improve the performance by using private buckets per block i.e. each block will have its private copy of buckets and each thread in a block will update its private copy. After that all the private buckets are merged into a single bucket.

The private buckets can be implemented using shared memory as they are 10x faster than DRAM global memory.#define BUCKETS 7 __global__ void cuda_histogram_privatization(char *s, int *histo, int n, int m, int b) { // private histogram copies held in shared memory __shared__ int histo_s[BUCKETS]; int index = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; // Since number of buckets can be greater than the number of threads in a block, each thread // initializes multiple buckets. for (int i = threadIdx.x; i < BUCKETS; i += blockDim.x) histo_s[i] = 0; __syncthreads(); if (index < n) { char c = s[index]; int c_int = c - 'a'; // update the private copy of buckets in shared memory atomicAdd(&(histo_s[c_int/b]), 1); } __syncthreads(); // update bucket in global memory with values from shared memory for (int i = threadIdx.x; i < BUCKETS; i += blockDim.x) { int cnt = histo_s[i]; if (cnt > 0) atomicAdd(&(histo[i]), cnt); } }

If the number of characters are too high, we might be spawning too many threads and worse if the distribution of buckets is skewed. One possible way to handle a lot of characters in the input is thread coarsening where a single thread is responsible for updating the histogram corresponding to multiple characters.#define BUCKETS 7 #define COARSE_FACTOR 16 __global__ void cuda_histogram_privatization_coarsening(char *s, int *histo, int n, int m, int b) { // private histogram copies held in shared memory __shared__ int histo_s[BUCKETS]; int index = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; // Since number of buckets can be greater than the number of threads in a block, each thread // initializes multiple buckets. for (int i = threadIdx.x; i < BUCKETS; i += blockDim.x) histo_s[i] = 0; __syncthreads(); // consecutive threads operates on consecutive elements as then the access to DRAM // is coalesced. for (int i = index; i < n; i += blockDim.x*gridDim.x) { char c = s[i]; int c_int = c - 'a'; // update private copy of buckets in shared memory atomicAdd(&(histo_s[c_int/b]), 1); } __syncthreads(); // update bucket in global memory with values from shared memory for (int i = threadIdx.x; i < BUCKETS; i += blockDim.x) { int cnt = histo_s[i]; if (cnt > 0) atomicAdd(&(histo[i]), cnt); } } int main() { int n = 1e5; int b = 4; int m = ceil(26.0/b); char *s; int *histo; cudaMallocManaged(&s, n*sizeof(char)); cudaMallocManaged(&histo, m*sizeof(int)); // generate some random stream of characters of size n here. for (int i = 0; i < m ; i++) histo[i] = 0; int n_threads = ceil(n/COARSE_FACTOR); cuda_histogram<<<ceil(n_threads/1024.0), 1024>>>(s, histo, n, m, b); cudaFree(s); cudaFree(histo); }

Another possible way to implement coarsening is to have each thread operate on multiple consecutive characters but in that case the access to DRAM is not coalesced. Note that in CPU, accessing consecutive elements by same thread is faster due to cache lines where once a block of 64 bytes data is loaded into cache, further request for same data is served from cache.

Similar to the parallel histogram problem above, one of the common problem involving reduction is vector summation. In vector dot product, we need to sum the products of individual elements of 2 vectors. One simple strategy is for each thread is to do anatomicAdd()on the output with the corresponding element from the input.__global__ void vector_sum(float *inp, float *out, int n) { int index = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; if (index < n) atomicAdd(out, inp[index]); }

After these we can optimize the above kernel by using techniques like memory coalescing, shared memory & tiling and thread coarsening. The problem with the above technique is that multiple threads writing to same location in either global memory or shared memory. Even with shared memory we have seen that bank conflicts can arise which effectively makes the addition serial instead of parallel.

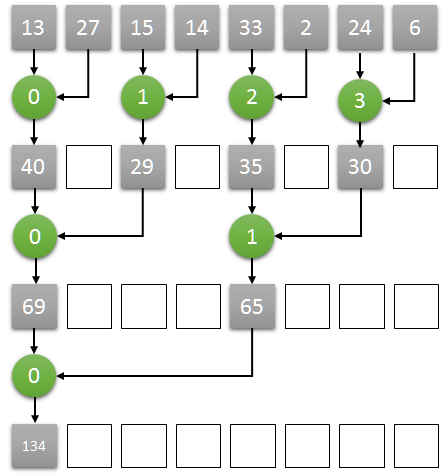

A concept similar to private buckets for parallel histogram is reduction trees for summation. Idea is that we will recursively calculate the sum. In the 1st stage, half of the threads will calculate the sum of 2 distinct locations and store the result in one of the locations. In the next stage, 1/4th the threads will again calculate the sum of 2 distinct locations those that were updated in the 1st stage and so on, until we will have one thread to calculate the final sum.

Thus to sum N input elements, there will be O(log(N)) stages and for each stage K, we will haveN/2^Kthreads each summing up 2 distinct locations updated in stage K-1. The below diagram highlights the reduction tree process.

The threads are assigned to even numbered indices of the input array as follows.:#define TILE_WIDTH 1024 __global__ void vector_sum_red_tree(float *inp, float *out, int n) { // shared memory holds inp elements twice the number of threads in block // for 1024 threads in block, shared memory size is 2048 __shared__ float out_s[2*TILE_WIDTH]; // size of inp vec in each block is 2*blockDim.x which is same as 2*TILE_WIDTH. // load the inp in shared memory // threads corresponds to the even indices in the shared memory array. int idx = 2*blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + 2*threadIdx.x; if (idx + 1 < n) out_s[2*threadIdx.x] = inp[idx] + inp[idx + 1]; else if (idx < n) out_s[2*threadIdx.x] = inp[idx]; else out_s[2*threadIdx.x] = 0.0f; __syncthreads(); for (int stride = 2; stride < 2*TILE_WIDTH; stride *= 2) { if (threadIdx.x % stride == 0) { if (2*threadIdx.x + stride < 2*TILE_WIDTH) out_s[2*threadIdx.x] += out_s[2*threadIdx.x + stride]; } __syncthreads(); } if (threadIdx.x == 0) atomicAdd(&out[0], out_s[0]); } int main() { int n = 1e6; float *a; float *b; cudaMallocManaged(&a, sizeof(float)*n); cudaMallocManaged(&b, sizeof(float)); b[0] = 0.0f; vector_sum_red_tree<<<ceil(n/float(2*TILE_WIDTH)), TILE_WIDTH>>>(a, b, n); cudaDeviceSynchronize(); std::cout << "Result: " << b[0] << std::endl; cudaFree(a); cudaFree(b); return 0; }

The above method doesn’t have very good resource utilization and have lot of control divergence because for further stages only a fraction of threads are used to calculate the sum. If in a warp of 32 threads, at-least one thread is used then the whole warp is active to consume GPU resources. But if no thread in a warp is active, it doesnt’t consume any GPU resource. Let’s look at one block of 1024 threads i.e. 32 warps working with 2048 elements of the input array.| Stage | # Active Threads | # Active Warps | # Thread Resources Consumed (# Active Warps * 32) | | ----- | ---------------- | -------------- | ------------------------------------------------- | | 1 | 1024 | 32 | 1024 | | 2 | 512 | 32 | 1024 | | 3 | 256 | 32 | 1024 | | 4 | 128 | 32 | 1024 | | 5 | 64 | 32 | 1024 | | 6 | 32 | 32 | 1024 | | 7 | 16 | 16 | 512 | | 8 | 8 | 8 | 256 | | 9 | 4 | 4 | 128 | | 10 | 2 | 2 | 64 | | 11 | 1 | 1 | 32 |

Thus the ratio of total number of active threads (sum of 2nd column) to total number of threads resource consumed (sum of last column) =(1+2+4+8+16+32+64+128+256+512+1024)/(32+64+128+256+512+1024*6) = 0.29.

In the 2nd method, the threads are assigned to consecutive indices of the input array.

#define TILE_WIDTH 1024 __global__ void vector_sum_red_tree_consecutive(float *inp, float *out, int n) { __shared__ float out_s[TILE_WIDTH]; int idx = 2*blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; // update shared memory array if (idx + TILE_WIDTH < n) out_s[threadIdx.x] = inp[idx] + inp[idx + TILE_WIDTH]; else if (idx < n) out_s[threadIdx.x] = inp[idx]; else out_s[threadIdx.x] = 0.0f; __syncthreads(); for (int stride = TILE_WIDTH/2; stride >= 1; stride /= 2) { if (threadIdx.x < stride) { if (threadIdx.x + stride < TILE_WIDTH) out_s[threadIdx.x] += out_s[threadIdx.x + stride]; } __syncthreads(); } if (threadIdx.x == 0) atomicAdd(&out[0], out_s[0]); }

In the 2nd method, resource utilization is better as compared to the 1st method. Let’s look at the same ratio as above.| Stage | # Active Threads | # Active Warps | # Thread Resources Consumed (# Active Warps * 32) | | ----- | ---------------- | -------------- | ------------------------------------------------- | | 1 | 1024 | 32 | 1024 | | 2 | 512 | 16 | 512 | | 3 | 256 | 8 | 256 | | 4 | 128 | 4 | 128 | | 5 | 64 | 2 | 64 | | 6 | 32 | 1 | 32 | | 7 | 16 | 1 | 32 | | 8 | 8 | 1 | 32 | | 9 | 4 | 1 | 32 | | 10 | 2 | 1 | 32 | | 11 | 1 | 1 | 32 |

Thus the ratio of total number of active threads to total number of threads resource consumed =(1+2+4+8+16+32+64+128+256+512+1024)/(32*6+64+128+256+512+1024) = 0.94.

Using thread coarsening we can further improve the thread re-usability of the above code as follows. Each block of thread works with 2*COARSE_FACTOR number of input elements. Coarsening is used only while loading the initial sums into shared memory array:#define TILE_WIDTH 1024 #define COARSE_FACTOR 2 __global__ void vector_sum_red_tree_coarsened(float *inp, float *out, int n) { __shared__ float out_s[TILE_WIDTH]; // each block of thread works with 2*COARSE_FACTOR number of // input elements. int idx = 2*COARSE_FACTOR*blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; // for each shared memory index array i, assign it the values // inp[i] + inp[i+TILE_WIDTH] + inp[i+2*TILE_WIDTH] + ... upto 2*COARSE_FACTOR float s = 0.0f; for (int i = idx; i < 2*COARSE_FACTOR*(blockIdx.x+1)*blockDim.x; i += TILE_WIDTH) { if (i < n) s += inp[i]; } out_s[threadIdx.x] = s; __syncthreads(); for (int stride = TILE_WIDTH/2; stride >= 1; stride /= 2) { if (threadIdx.x < stride) { if (threadIdx.x + stride < TILE_WIDTH) out_s[threadIdx.x] += out_s[threadIdx.x + stride]; } __syncthreads(); } if (threadIdx.x == 0) atomicAdd(&out[0], out_s[0]); }

In the next few parts of the series we will take a look at some common algorithmic problems and how to solve them using parallel algorithms and CUDA and optimize the performances. We will also look at some key GPU concepts related to deep learning such as cuDNN, cuBLAS, Tensor Cores and Kernel Fusion along the way.